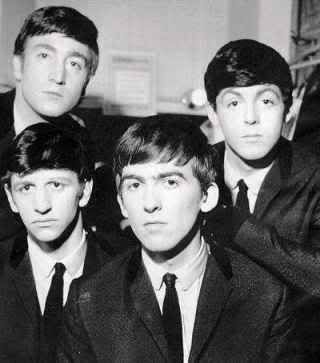

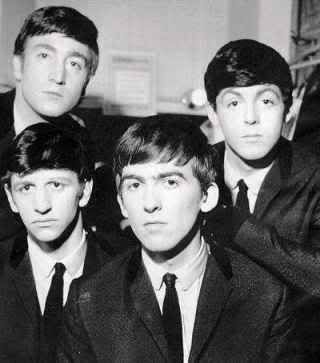

This will have you rockin and rollin. All the way back to the 60s.

This will have you rockin and rollin. All the way back to the 60s.

This is a must fucking watch.

This is a must fucking watch.

Swapping Places.

The silence of the class was disrupted by an intervention. It was the test for chemistry, one I could never understand because I never bothered to. I wasn’t going to be a rocket scientist, nor was I going to be working in a pharmacy. The steps that followed were the steps I doubt I would ever forget.

“There’s been an emergency at home. I think its best that you go back.”

And so I did. Yet the thoughts that ran through my brain were the exemption I would get from chemistry, not what was waiting for me at home. I opened the wooden door that now seemed strangely unfamiliar. The living room was exactly the way it was, polished, clean and a certain smell that marinated the room with rancor. The only thing that was missing was my mother sitting on the couch, sipping on black coffee and semi toasted bread with scrambled eggs. She would read the newspaper and for many reasons I never understood, have the television on at the same time.

I entered her room and what greeted me was a sea of hopelessness, the kind that kids my age would have. The doctor had spoken of the time left. Her systems were failing and her time was almost up. My mother had decided to come home to return home. She had the choice of a hospice or the hospital but the alleyways that were the crossroads of going home were far too depressing for her. Now I would go on about the things I did in that 5 hours but to sum it up, I did nothing much a filial son would do. My mother lasted past the 5 hours past the night till the next day. I had gone back into the room when all were asleep at about 2 am in the morning after the “5 hour scare”. I spoke to her of the many things that happened in school and I spoke to her of the many things that I would have never said. No reply. I had told her I loved her. No reply. I had told her that I was sorry for wearing a mask in front of her at times and I was sorry for choosing my friends over her and that I was sorry for not being the son I should have been. No reply.

It was 415 in the afternoon the next day. The bed had seemed smaller with the crowds of people that surrounded her. She could not speak. Maybe she could hear but her systems were failing and the flam that filled her throat had to be taken out using suction. She had no strength to cough them out. She was weak and the end seemed near. Her eyes could not open and anything that happened against what I had mentioned above would mean an immense amount of strength.

She had waited for us three children to come around, to all be present and hold on to her hand. They were cold, and that coldness sent chills down my spine. It gave my anatomy a kind of weakness I would remember for life. You’d call it guilt or maybe an inner torture. I’d call it fucked up. She opened her eyes and looked us dead in the eye. She held on tight to our hands with such strength that I could not believe what was happening before me. Then it happened. Her eyes would close, never to open again. She had left with a tear that streamed down her face. To this day I don’t know if other people saw that tear. I question what that tear was. Perhaps it was an unwillingness to leave, the kind that would exemplify her worries or problems that were to come after her ascending. I held on to her lifeless hand, refusing to let go. Everybody was crying except me. The tears wouldn’t come out and my heart wouldn’t settle. I would insist she was not gone and that self fulfilling prophecy, to all of you, would probably be a joke. And so it was that on the First of March 2003, I said goodbye.

“Are you sick mom?”

“I’m going home soon. It’s not a bad thing dear. It’s just life.”

“Will you come back to visit me? I don’t want you to go.”

“I’m proud of you and we’ll always meet in our dreams; on the beach, at home, botanic gardens. You’ll find me there, I promise.”

The stream of black coats entering the church seemed never to end. Accompanying them was an equal number of black dresses and veils, all crowding beneath the ancient stones of the church. Once the news had gone out about her death, it was difficult to keep up with the phone calls. The town was very small, and must have seemed flooded by black and mourning. The church was the same that she had been married in. It was set off from the road on a large property, quaint and simple beneath the sun. The exterior was made up of large stones and brick, patterned in a fashion very common among the older buildings.

The casket was being led through the front door when I arrived .The pall bearers were sturdy men, the same age as she would have been, all from the same fraternity of their college days. They carried both her and the weight of realization on their backs. It appeared a very heavy load. The casket was polished cherry-wood, very elegant under the cloudless sky. It disappeared into the doors of the church, swallowed up in the maw of that great building.

Others were coming, and we entered the building in slow procession. Now we too were being swallowed up, consumed by the feelings and sentiments surrounding the occasion. Anyone who enters the room of a funeral somehow loses himself, and cannot feel anything except within certain, accepted parameters: thoughtfulness, grief or despair.

Something similar happens at weddings. While rehearsing, everything seems so ridiculous and funny, and people cannot help but laugh at the absurdity of it all. But during the wedding, such emotions are impossible, because they are curtailed by the decorous expectations of the multitude.

Finally the event began. The solemn words and the expressive tears made it apparent that she was dearly missed. One speaker followed another, almost every one coming from the front of the pews. Then one of them stood up whom I remember quite clearly, since his words struck me as being different in tone from the rest. Perhaps it would be best to describe it exactly.

He walked to the podium with very audible footsteps, which contrasted the almost fluid motion of his arms and legs. He seemed to float to the center of the area where all eyes were focused, accompanied by the tiny chatter of his footsteps. He stood behind the stand, which was meant more as an emotional defense than for any particular purpose. His feet were placed heavily, and it seemed that his body sank into position. I remember that the last breath he let out, before he began to speak, seemed to consider all of us, acknowledging our devotion in a way, agreeing with the tragedy of the event. Then he spoke.

"I'm not sure what I should say to all of you. It touches me that you've come. I only wish I could greet you under different circumstances.

"I expect that good form here is to say something touching. But I have nothing to say because I never really knew my mother. In fact, all she was to me then was a woman that would give me what I want, when want." He took a breath, and held it long.

"None of you in the audience has ever been struck by me. I know this because since my childhood I have never struck anyone except my mother. I can't explain why, or what motivated it. I do know she believed in me and yet never once did return that kindness. "

"And so I never met the best part of her. Instead she showed it to you, her friends, the family that bothered to care. But I, who should have known her best, lost my chance because I was ignorant of what was really important."

"That's why I have nothing to say to you today. But I am grateful to you for being here, since now I can meet with that part of her which touched the hearts of others; that part I always knew was there from afar, but never met. In your eyes I can see reflected the joys she shared with you, and the magnanimity of her heart.

"Thank you again for coming, and acquainting me with who my mother was."

He lowered his head and only stared at his fingers. He must have felt pinned, even though none of us would have judged him badly. Who hadn't done such things?

But he raised his head again, and in his eyes there was more to be said. He fought with it. I could see his lips moving slightly, and then looked down again. But shortly afterward he began to speak.

"I guess the only thing I can say is that I've learned something from this; that the day will come when an opportunity can be lost, and that the people closest to you, you realize never knew, not because they were hard to understand, but because we chose not to. What's worse is that we may never know them, as we hope foolishly for a magical day to come when everything will be forgotten. But that day never comes. It didn’t for me and I know that now."

He shook his head and stopped speaking abruptly and looked down again. I think he understood the negative impression he had created, but it seemed beyond his power to transition into something more hopeful. Maybe he felt that an anecdote, or some word of optimism, would make too much light of the experience he was trying to share. In either case, he turned away from the podium and walked back to his place. And sitting down he kept his eyes to the floor, never raising them, with the same expression of thought always on his face.

Was he trying to resurrect some past memory that might exonerate his misdeeds, which he had now confessed? Yet he never moved, not through the next speaker or the one after; it was not until the final words were said that he stood and departed from the room and its oppression.

The atmosphere was one indescribable, so much so that one's thoughts could not be translated into language. The room was dead silent as many prepared to say their final words to a lady that played a major role in their lives. As they took turns to view the open coffin and placed roses into it, a sense of guilt rid into the heart of that young man. He carried his way through and said his final words to that very someone whom he had loved so very much but never had the chance to tell or like I said, that he never took the chance on his own.

Any time I saw him after that, I could always detect, if I looked hard enough at his movements and his eyes, the impression of that day. Perhaps it was in this way that his mother had finally become a part of him: a gift as he later told me, because his mother had indirectly taught him a very important lesson about the relationships between people; Something which the memory of that day would never let him forget.

I miss you